| Previous Date | Day By Day Index | 16th OVI Home Page | Next Date |

Where was the regiment on

Monday, December 29, 1862

This is, indeed, the darkest day in the history of the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. This day would see Col. John F. DeCourcey move his brigade toward Walnut Hills, the highly fortified bluffs looming over the river valley and Chickasaw Bayou. General William Sherman's movements were highly complex, as he probed various points along the bluffs for any weakness that could be exploited, all in an attempt to break through the Confederate defenses and take Vicksburg for the Union. It could have been any brigade or regiment that ended up taking the heat of the battle, but, on this day, it was DeCourcey's brigade, and the 16th Ohio that filled that role.

The 16th Ohio and 54th Indiana were positioned on the north side of the road near and parallel to Chickasaw Bayou, forming the left flank of DeCourcey's brigade. When the orders were given to advance, the 16th moved forward over the bayou and toward the bluffs. The Rebels had rifle pits along Valley Road which ran along the bottom of the bluffs. Behind them, protected and mostly hidden in the trees at the base of the bluffs were a multitude of enemy batteries, all in perfect position to sweep the fields below. The 16th made some progress, under withering fire. The move was supposed to be in concert with advances by General Blair's 1st brigade to the left and on the other side of the bayou along with advances by General Thayer's 3rd Brigade on the right flank to the south. Because the water in the bayou (McNutt Lake) which lay between the Union troops and the bluffs was deeper than expected, along with a mass of fallen trees and brush, all forming a nearly impenetrable blockade, the other brigades were unable to reach the Confederate line in time to match DeCourcey's advance (DeCourcey having the easier crossing at a corduroy bridge carrying the road across to the bluffs). Many and various attempts were made by Sherman's commanders to find ways across the bayou but were never successful enough to enable a uniform attack, in most cases, causing the Union troops to become pinned down and in terrible cross fires of enemy bullets and cannon shells. The Confederates were able to concentrate massive firepower on the 16th Ohio and 54th Indiana, the advance regiments in the battle. The troops became pinned down along the southern edge of the bayou (McNutt Lake) and in the field in front, unable to cross the deep water or to return across the corduroy bridge since this would require outright exposure to the Rebel defenders. History tells us that several times a soldier placed a 'white flag' on their gun and attempted to surrender. Each time, Captain Milton Mills, Company D (and the web author's great great grandfather), pinned down with the men, ordered the soldier to take down the flag. Ultimately, however, there was no way out for most of the troops that had reached the furthest point of advance and those that were alive were compelled to surrender.

To understand the true feeling and actions of the 16th Ohio on this day, here is what Cpl. Theodore Wolbach, Company E, recalls:

(in the dawn of December 29th...) The boys stirred around. Some gathered fuel and made coffee a short distance to the rear; others were contented with bacon and hardtack. There was a good degree of cheerfulness and every shell that went tearing through the woods and every bullet that zipped close brought forth a humorous remark. As the light increased and the fog rose the firing on the skirmish line increased, but there were no other demonstrations until near noon, when the staff officers became unusually active, galloping from one command to another, transmitting the orders of their superiors. Men that had strayed away short distances were called into ranks. The various regiments were formed in column of company or divisions and remained in that position awaiting further orders. In the 16th there were about seven hundred men present for duty, well clothed and equipped and in splendid condition. After this day's work the regiment could never again muster in such force.

The Confederates in their works along the bluffs were noticed to be active. Their position had been strengthened during the night. Fresh earth had been thrown up and room made for more troops and artillery. When we looked across the intervening space at the formidable preparations and understood that we were soon to be sent forth in an attempt to storm and capture the position, it was perfectly easy for the soldiers to feel a little peculiar.

Shortly before the signal for the advance, Gen. Geo. W. Morgan rode up in front of our regiment and briefly addressed us. His voice had the tone of excitement, though he spoke clearly and with great assurance. The writer vividly remembers the substance of that speech. The General exhorted us to move promptly when we received the order, and walk right up and plant our colors on the top of the hill. His remarks had an enervating and peculiar effect on one of our new men, who sunk down groaning and in agony. A few minutes afterward we marched away and left him lying pale and weak, the result perhaps of intense nervous excitement.

Morgan went to each of the regiments of our Brigade and made short speeches. The motive was prompted by patriotism and was correct, but the effort seemed out of place in the face of existing circumstances. When the soldier has a bloody job on hand I think he prefers to be ordered at it without any superfluous talk.

A while before we were called into ranks, some troops without knapsacks and in light marching order, came up to the edge of the woods where we had halted. They were the 13th Illinois Infantry, and belonged to Blair's Brigade. They had been sent here by mistake. About facing, they marched back, crossed the Chickasaw Bayou in the rear of us and took position in the dense wood to our left.

About one o'clock p.m. the order was given and we advanced. Solid and compact we passed through the forest and entered the slashing in the face of hot artillery fire. The regiments preserved tolerable good order, passing over and around the huge fallen trees. The bayou was reached and crossed with some difficulty and confusion. As the men swarmed into the open space beyond, they received a furious musketry fire from the Confederate infantry in the earth-works in the immediate front and in point-blank range. The effect of the fire on the advancing troops was fearful. At every beat of the pulse scores of the exposed Federals sunk to the muddy earth, dead or with weakening wounds, yet there was an effort on the part of the officers to keep up a semblance of order. It was too plainly evident that the blazing rifle-pits, backed by entrenched batteries, were obstacles that could not be carried by broken regiments. To storm these works the troops must reach them in good order and superior numbers. The energetic resistance of the enemy broke the force of the charge so effectually that the men faltered and gave ground. The bulk of the brigade fell back to the bayou and beyond. Many laid down on the field, in little depressions or behind such covering as was handy. Many of these were so completely covered by the rebel infantry fire that they were compelled to lay low and reluctantly surrender to the enemy afterward. Gen. Frank Blair's Brigade went in on the left of us and shared a similar fate.

The thrilling and peculiar incidents of this charge would furnish an exciting chapter in the history of this ill-fated expedition.

The regiments of our brigade that participated in this affair were the 54h Indiana, 22nd Kentucky, and 42nd and 16th Ohio. DeCourcey was opposed to making this charge, and it has been said that when his men passed him on their way to the front he expressed himself in terms of regret. Some of the wounded, that lay helpless between the lines and could not be removed, were shot the second or third time. Some of our men insisted that this was done intentionally by the enemy, but it is hoped that they were not so barbarous. Some poor fellows attempted to get up and walk, but weak from the loss of blood, they would stagger and fall. Others tried to drag their blood-stained bodies or roll themselves toward our lines. Some succeeded in getting back to points of safety in this manner. The majority of these recovered, and a few of them are alive today. The wounded men of our regiment, that fell into the enemy's hands, fared badly. In dressing the wounds or performing operations, the rebel surgeons were careless and rough. Jobe, a young fellow, a recent recruit of Co. I, had a bad wound in the leg. While the rebel surgeons were at work amputating the limb, the supper call beat, and the unfeeling wretches postponed work on the operations until after the meal. The poor fellow's sufferings soon brought death. Shank, of Co. B, who had a bullet lodged in his head was similarly abandoned when the ball was almost extracted. He recovered.

The commanding officers of the 16th Ohio and 22nd Kentucky, Kershner and Monroe, were both wounded, the former in the arm and the later in the head. Kershner was captured. Two captains of the 22d and one of the 16th (G. W. Harn, of Co. I,) were killed. Many of the line officers were wounded.

An exploding shell tore the flag of the 22d Kentucky into shreds. The color-bearer, a noble looking Hungarian commonly known as 'Nick,' frightened and bewildered, threw the staff away and would never afterward carry the colors. They were eagerly snatched up and carried through the fight by a young corporal, who was afterward rewarded for the act by a Lieutenancy.

Two of the 16th boys had their rifles knocked out of their hands and badly bent, one of them nearly double. Another had the butt of his gun struck and shattered to pieces. Lieutenant Ross, of Co. G, was shot in the face, the ball taking a downward course, damaging the palate to such an extent that it became necessary afterward to insert a plate to restore articulation of speech. Jonathan Wright, of Co. E, was struck on the side of the head by the leaden fuse plate of a shell. It broke the jaw-bone badly and embedded itself firmly in the side of the face, but was successfully removed by Surgeon Brashear, the piece weighing four ounces.

It was a mortifying spectacle to us to see the exultant Confederates, marching our comrades as prisoners of war, over the distant hill toward Vicksburg, and as a further aggravation, some of these regiments that were fighting us here were a part of the same force that we had met at Tazewell, Tennessee.

During the night of the 29th, the 'tooting' of the locomotives and the cheering of our enemy, assured us that they were getting reinforcements. Several of their cornet bands, on the bluffs, discoursed music until a late hour. They played the national airs of the Confederacy. 'Bonnie Blue Flag' appeared to be conspicuous and was loudly cheered by their men. 'Home Sweet Home' drew applause from our side. When they struck up 'Get out of the Wilderness,' we felt the humiliating force of the joke, but we responded with vociferous cheers.

* Information and italicized quotations above from a series of articles entitled Camp and Field - The Old 16th Ohio, written in the 1880s by Theodore Wolbach, late Corporal in Company E, 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

A stirring account of the peak of the battle by Sgt. Jesse E. Leasure, Company G, written in 1884 and with responses to the battle account written about the same time by Pvt. Frank Mason of the 42nd Ohio (see full account):

Up the ban and over that terrible field of death without faltering went the 16th Ohio and 22d Ky., till the number in the 16th was reduced from 730 to 134. We never fell back against the 22d Ky., for that noble old regiment was abreast of our () vainly striving with us to reach the rebel works. When we were within about 60 yards of the first line, from the sheer force of the terribly-destructive fire of the enemy, we all dropped flat on the earth, where we were slightly covered by a rise in the ground. There was, however, no confusion about it. Men dropped along the route from wounds, death and fatigue, till we could not go any farther, and then we stopped. The rebels did not run out of their works and take us in, as Mason and Fry say, but a squad of cavalry came charging in, and just then I thought of what my father had told me when leaving home - Don't come home with a bullet in your back. I had faced the music so far and got no bullets in front, and thought I would risk the chance of getting one in the rear. It was a desperate race, and I know it did not take me as long to get back as it did forward.

This photo was titled Chickasaw Bayou, Mississippi, The poison spring. Battlefield of Chickasaw Bayou by the photographer William Redish Pywell. Although the published date on the photograph is February, 1864, it is assumed to have been taken at the time of or shortly after the battle in December, 1862. It appears to show a wagon, limber or caisson partially submerged in water at the bottom of what is assumed to be either Chickasaw Bayou or McNutt Lake (see maps). Amazingly, there also appears to be the body of a soldier lying in the mud beyond and just above the wagon wheel. If this photo is correctly identified, it may be the only known image of the Chickasaw Bayou battlefield at or near the time of the battle. The terrain certainly matches the various descriptions of the bayou and surrounding landscape.

Library of Congress Photo

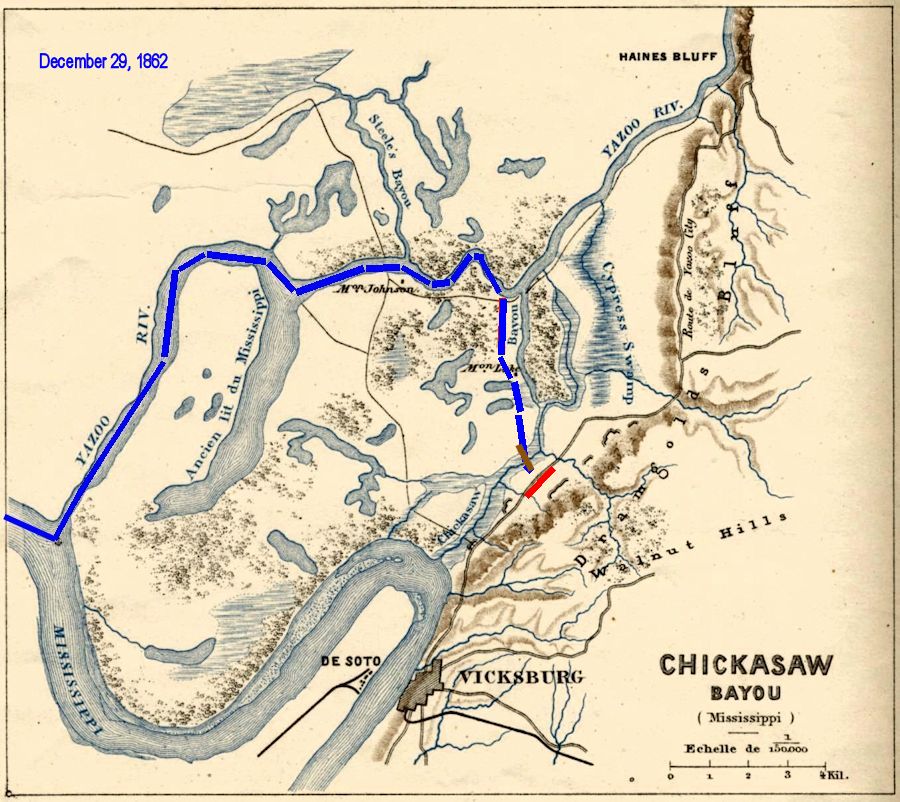

Period map showing the movement of DeCourcey's brigade, south, along Chickasaw Bayou and toward Chickasaw Bluffs or Walnut Hills. The red line indicates location of a battery of Rebel field artillery and troops on the north side of the bayou (McNutt Lake or Fishing Lake). Chickasaw Bayou, which runs south from the Yazoo River, turns to the east at the junction with McNutt Lake. Please remember the annotations on this map only show the movement of Col. John F. DeCourcey's 3rd Brigaded under Gen. George W. Morgan's Third Division. To get a full description of all the operations of Sherman's force at Chickasaw Bayou, please review the Chickasaw Bayou battle page.:

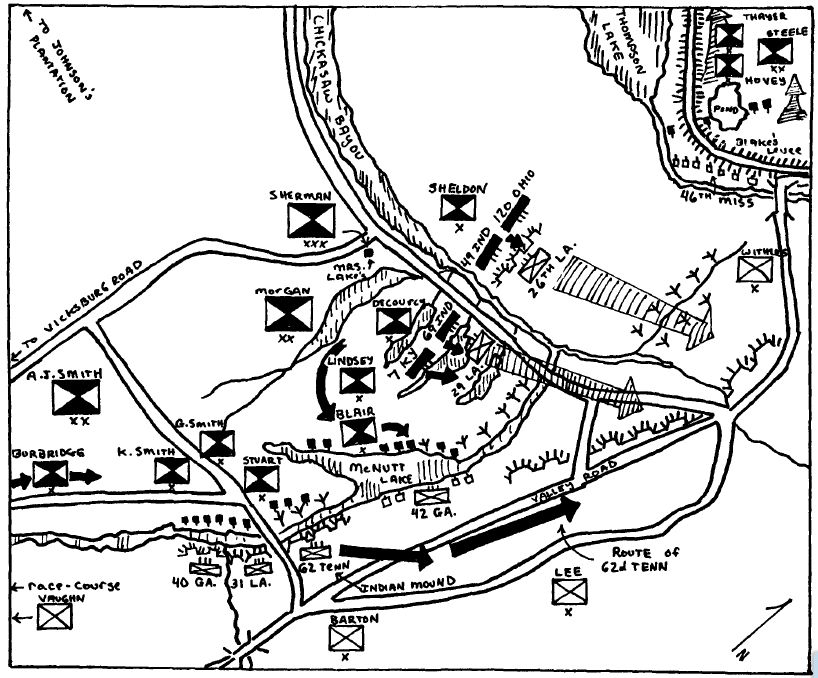

A more detailed map showing the locations of Union and Confederate forces on December 29, 1862.

map drawn by Major Gray M. Gildner, U. S. Army, 1991

| Previous Date | Day By Day Index | 16th OVI Home Page | Next Date |