| Camp & Field Chapter 39 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 41 |

The Camp & FieldArticles by Theodore Wolbach |

Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach |

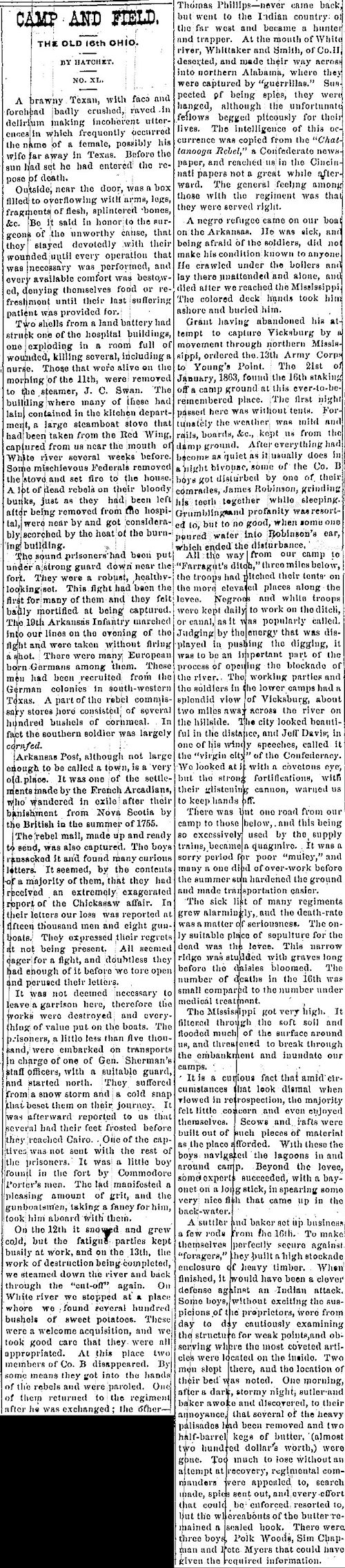

The following image represents one of a series of articles written by Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach, Company E, titled "Camp and Field" and published, by chapter, in the Holmes County Republican newspaper from February 24, 1881 to August 17, 1882. The articles tell the story, in great detail and color, of the 16th OVI, from the inception of the 3-year regiment in October, 1861, through all its camps, battles and marches until it was disbanded on October 31, 1864. The first 35 chapters, also presented on these pages, were obtained from a book in which the articles, clipped from the newspaper, had been pasted over the pages, believed to have been done by a descendant of Capt. Rezin Vorhes, Company H. All the remaining chapters (36 through 78), except chapter 60, were recently found in a Holmes County library by researcher Rob Garber who obtained copies, performed the transcriptions and provided to this website and which are also presented here, thus providing the complete work by Theodore Wolbach.

Throughout these articles click on the underlined white text for additional details.

The webauthor thanks 16th Ohio descendant Rob Garber for his excellent research on the Camp And Field articles and for performing the tedious digital transcription of those articles found on each page. The transcriptions were made to reflect the original articles verbatim, misspellings and all. Rob is the 3rd great nephew of Capt. William Buchanan, Company F, 16th Ohio, who served in the 90-day regiment as a private, re-enlisting in the three year regiment, and eventually making the rank of Captain of Company F. Thanks Rob!

Chapter 40 - January, 1863

|

Published in Holmes County Republican XL. A brawny Texan, with face and forehead badly crushed, raved in delirium making incoherent utterances in which frequently occurred the name of a female, possibly his wife far away in Texas. Before the sun set he had entered the repose of death. Outside, near the door, was a box filled to overflowing with arms, legs, fragments of flesh, splintered bones, &c. Be it said in honor to the surgeons of the unworthy cause, that they stayed devotedly with their wounded until every operation that was necessary was performed, and every available comfort was bestowed, denying themselves food or refreshment until their last suffering patient was provided for. Two shells from a land battery had struck one of the hospital buildings, one exploding in a room full of wounded, killing several, including a nurse. Those that were alive on the morning of the 11th, were removed to the steamer J.C. Swan. The building where many of these had lain, contained in the kitchen department, a large steamboat stove that had been taken from the Red Wing, captured from us near the mouth of White river several weeks before. Some mischievous Federals removed the stove and set fire to the house. A lot of dead rebels on their bloody bunks, just as they had been left after being removed from the hospital, were near by and got considerably scorched by the heat of the burning building. The sound prisoners had been put under a strong guard down near the fort. They were a robust, healthy-looking set. This fight had been the first for many of them and they felt badly mortified at being captured. The 19th Arkansas Infantry marched into our lines on the evening of the fight and were taken without firing a shot. There were many European born Germans among them. These men had been recruited from the German colonies in south-western Texas. A part of the rebel commissary stores here consisted of several hundred bushels of cornmeal. In fact the southern soldier was largely cornfed. Arkansas Post, although not large enough to be called a town, is a very old place. It was one of the settlements made by the French Arcadians, who wandered in exile after their banishment from Nova Scotia by the British in the summer of 1755. The rebel mail, made up and ready to send, was also captured. The boys ransacked it and found many curious letters. It seemed, by the contents of a majority of them, that they had received an extremely exagerated [sic] report of the Chickasaw affair. In their letters our loss was reported at fifteen thousand men and eight gunboats. All seemed eager for a fight, and doubtless they had enough of it before we tore open and perused their letters. It was not deemed necessary to leave a garrison here, therefore the works were destroyed and everything of value put on the boats. The prisoners, a little less than five thousand, were embarked on transports in charge of one of Gen. Sherman's staff officers, with a suitable guard, and started north. They suffered from a snow storm and a cold snap that beset them on their journey. It was afterward reported to us that several had their feet frosted before they reached Cairo. One of the captives was not sent with the rest of the prisoners. It was a little boy found in the fort by Commodore Porter's men. The lad manifested a pleasing amount of grit, and the gunboatsmen, taking a fancy for him, took him aboard with them. On the 12th it snowed and grew cold, but the fatigue parties kept busily at work, and on the 13th, the work of destruction being completed, we steamed down the river and back through the |

Thomas Phillips--never came back, but went to the Indian country of the far west and became a hunter and trapper. At the mouth of White river, Whittaker and Smith, of Co. H, deserted, and made their way across into northern Alabama, where they were captured by A negro refugee came on our boat on the Arkansas. He was sick, and being afraid of the soldiers, did not make his condition known to anyone. He crawled under the boilers and lay there unattended and alone, and died after we reached the Mississippi. The colored deck hands took him ashore and buried him. Grant having abandoned his attempt to capture Vicksburg by a movement through northern Mississippi, ordered the 13th Army Corps to Young's Point. The 21st of January, 1863, found the 16th staking off a camp ground at this ever-to-be-remembered place. The first night passed here was without tents. Fortunately the weather was mild and rails, boards, &c., kept us from the damp ground. After everything had become as quiet as it usually does in a night bivouac, some of the Co. B boys got disturbed by one of their comrades, James Robinson, grinding his teeth together while sleeping. Grumbling and profanity was resorted to, but to no good, when some one poured water into Robinson's ear, which ended the disturbance. All the way from our camp to There was but one road from our camp to those below, and this being so excessively used by the supply trains, became a quagmire. It was a sorry period for poor The sick list of many regiments grew alarmingly, and the death-rate was a matter of seriousness. The only suitable place of sepulture for the dead was the levee. This narrow ridge was studded with graves long before the daisies bloomed. The number of deaths in the 16th was small compared to the number under medical treatment. The Mississippi got very high. It filtered through the soft soil and flooded much of the surface around us and threatened to break through the embankment and inundate our camps. It is a curious fact that amid circumstances that look dismal when viewed in retrospection, the majority felt little concern and even enjoyed themselves. Scows and rats were built out of such pieces of material as the place afforded. With these the boys navigated the lagoons in and around camp. Beyond the levee, some experts succeeded, with a bayonet on a long stick, in spearing some very nice fish that came up in the back-water. A suttler and baker set up business a few rods from the 16th. To make themselves perfectly secure against |

| Camp & Field Chapter 39 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 41 |