| Camp & Field Chapter 40 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 42 |

The Camp & FieldArticles by Theodore Wolbach |

Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach |

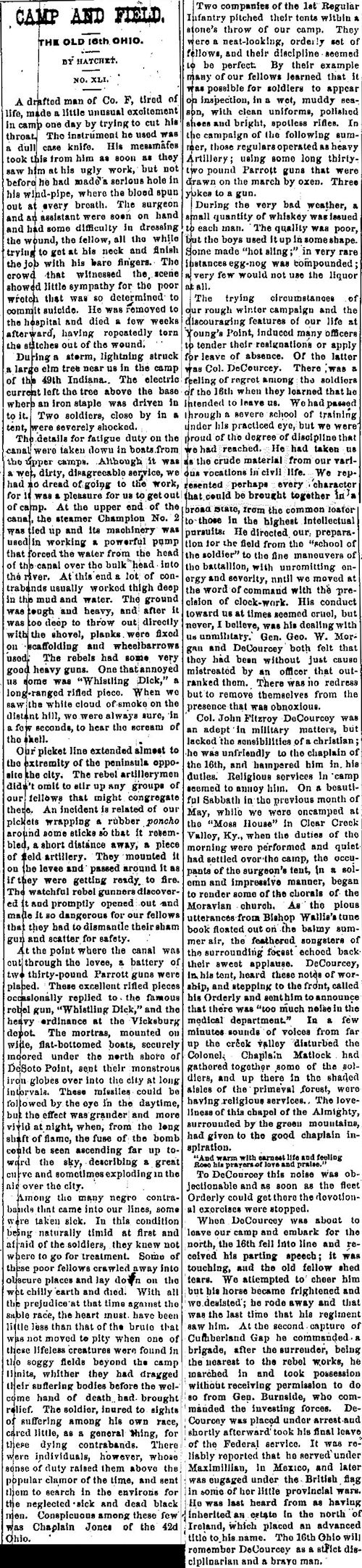

The following image represents one of a series of articles written by Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach, Company E, titled "Camp and Field" and published, by chapter, in the Holmes County Republican newspaper from February 24, 1881 to August 17, 1882. The articles tell the story, in great detail and color, of the 16th OVI, from the inception of the 3-year regiment in October, 1861, through all its camps, battles and marches until it was disbanded on October 31, 1864. The first 35 chapters, also presented on these pages, were obtained from a book in which the articles, clipped from the newspaper, had been pasted over the pages, believed to have been done by a descendant of Capt. Rezin Vorhes, Company H. All the remaining chapters (36 through 78), except chapter 60, were recently found in a Holmes County library by researcher Rob Garber who obtained copies, performed the transcriptions and provided to this website and which are also presented here, thus providing the complete work by Theodore Wolbach.

Throughout these articles click on the underlined white text for additional details.

The webauthor thanks 16th Ohio descendant Rob Garber for his excellent research on the Camp And Field articles and for performing the tedious digital transcription of those articles found on each page. The transcriptions were made to reflect the original articles verbatim, misspellings and all. Rob is the 3rd great nephew of Capt. William Buchanan, Company F, 16th Ohio, who served in the 90-day regiment as a private, re-enlisting in the three year regiment, and eventually making the rank of Captain of Company F. Thanks Rob!

Chapter 41 - February, 1863

|

Published in Holmes County Republican XLI. A drafted man of Co. F, tired of life, made a little unusual excitement in camp one day by trying to cut his throat. The instrument he used was a dull case knife. His messmates took this from him as soon as they saw him at his ugly work, but not before he had made a serious hold in his wind-pipe, where the blood spun out at every breath. The surgeon and an assistant were soon on hand and had some difficulty in dressing the wound, the fellow, all the while trying to get at is neck and finish the job with his bare fingers. The crowd that witnessed the scene showed little sympathy for the poor wretch that was so determined to commit suicide. He was removed to the hospital and died a few weeks afterward, having repeatedly torn the stitches out of the wound. During a storm, lightning struck a large elm tree near us in the camp of the 49th Indiana. The electric current left the tree above the base where an iron staple was driven in to it. Two soldiers, close by in a tent, were severely shocked. The details for fatigue duty on the canal were taken down in boats from the upper camps. Although it was a wet, dirty, disagreeable service, we had no dread of going to the work, for it was a pleasure for us to get out of camp. At the upper end of the canal, the steamer Champion No. 2 was tied up and its machinery was used in working a powerful pump that forced the water from the head of the canal over the bulk head into the river. At this end a lot of contrabands usually worked thigh deep in the mud and water. The ground was tough and heavy, and after it was too deep to throw out directly with the shovel, planks were fixed on scaffolding and wheelbarrows used. The rebels had some very good heavy guns. One that annoyed us some was Our picket line extended almost to the extremity of the peninsula opposite the city. The rebel artillerymen didn't omit to stir up any groups of our fellows that might congregate there. An incident is related of our pickets wrapping a rubber poncho around some sticks so that it resembled, a short distance away, a piece of field artillery. They mounted it on the levee and passed around it as if they were getting ready to fire. The watchful rebel gunners discovered it and promptly opened out and made it so dangerous for our fellows that they had to dismantle their sham gun and scatter for safety. At the point where the canal was cut through the levee, a battery of two thirty-pound Parrott guns were placed. These excellent rifled pieces occasionally replied to the famous rebel gun, Among the many negro contrabands that came into our lines, some were taken sick. In this condition being naturally timid at first and afraid of the soldiers, they knew not where to go for treatment. Some of these poor fellows crawled away into obscure places and lay down on the wet chilly earth and died. With all the prejudice at that time against the sable race, the heart must have been little less than that of the brute that was not moved to pity when one of these lifeless creatures were found in the soggy fields beyond the camp limits, whither they had dragged their suffering bodies before the welcome hand of death had brought relief. The soldier, inured to sights of suffering among his own race, cared little, as a general thing, for these dying contrabands. There were individuals, however, whose sense of duty raised them above the popular clamor of the time, and sent them to search in the environs for the neglected sick and dead black men. Conspicuous among these few was Chaplain Jones of the 42d Ohio. |

Two companies of the 1st Regular Infantry pitched their tents within a stone's throw of our camp. They were a neat-looking, orderly set of fellows, and their discipline seemed to be perfect. By their example many of our fellows learned that it was possible for soldiers to appear on inspection, in a wet, muddy season, with clean uniforms, polished shoes and bright, spotless rifles. In the campaign of the following summer, those regulars operated as heavy Artillery; using some long thirty-two pound Parrott guns that were drawn on the march by oxen. Three yokes to a gun. During the very bad weather, a small quantity of whiskey was issued to each man. The quality was poor, but the boys used it up in some shape. Some made The trying circumstances of our rough winter campaign and the discouraging features of our life at Young's Point, induced many officers to tender their resignations or apply for leave of absence. Of the latter was Col. DeCourcey. There was a feeling of regret among the soldiers of the 16th when they learned that he intended to leave us. We had passed through a severe school of training under his practiced eye, but we were proud of the degree of discipline that we had reached. He had taken us as the crude material from our various vocations in civil life. We represented perhaps every character that could be brought together in a broad State, from the common loafer to those in the highest intellectual pursuits. He directed our preparation for the field from the Col. John Fitzroy DeCourcey was an adept in military matters, but lacked the sensibilities of a Christian; he was unfriendly to the chaplain of the 16th, and hampered him in his duties. Religious services in camp seemed to annoy him. On a beautiful Sabbath in the previous month of May, while we were encamped at the

To DeCourcey this noise was objectionable and as soon as the fleet Orderly could get there the devotional exercises were stopped. When DeCourcey was about to leave our camp and embark for the north, the 16th fell into line and received his parting speech; it was touching, and the old fellow shed tears. We attempted to cheer him but his horse became frightened and we desisted; he rode away and that was the last time that his regiment saw him. At the second capture of Cumberland Gap he commanded a brigade, after the surrender, being the nearest to the rebel works, he marched in and took possession without receiving permission to do so from Gen. Burnside, who commanded the investing forces. DeCourcey was placed under arrest and shortly afterward took his final leave of the Federal service. It was reliably reported that he served under Maximillian, in Mexico, and later was engaged under the British flag in some of her little provincial wars. He was last heard from as having inherited an estate in the north of Ireland, which placed an advanced title to his name. The 16th Ohio will remember DeCourcey as a strict disciplinarian and a brave man. |

| Camp & Field Chapter 40 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 42 |