| Camp & Field Chapter 65 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 67 |

The Camp & FieldArticles by Theodore Wolbach |

Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach |

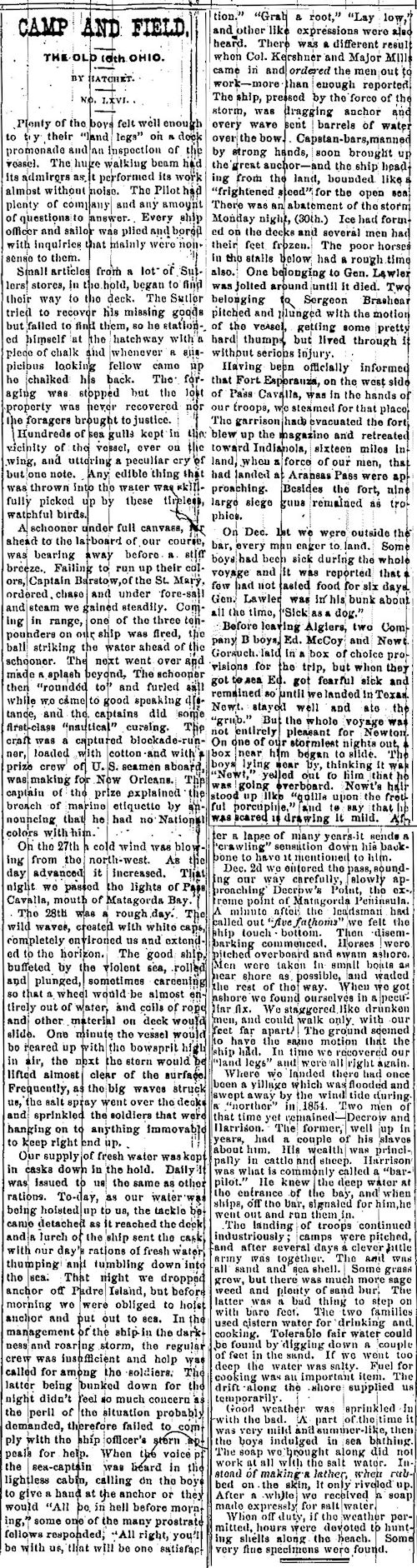

The following image represents one of a series of articles written by Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach, Company E, titled "Camp and Field" and published, by chapter, in the Holmes County Republican newspaper from February 24, 1881 to August 17, 1882. The articles tell the story, in great detail and color, of the 16th OVI, from the inception of the 3-year regiment in October, 1861, through all its camps, battles and marches until it was disbanded on October 31, 1864. The first 35 chapters, also presented on these pages, were obtained from a book in which the articles, clipped from the newspaper, had been pasted over the pages, believed to have been done by a descendant of Capt. Rezin Vorhes, Company H. All the remaining chapters (36 through 78), except chapter 60, were recently found in a Holmes County library by researcher Rob Garber who obtained copies, performed the transcriptions and provided to this website and which are also presented here, thus providing the complete work by Theodore Wolbach.

Throughout these articles click on the underlined white text for additional details.

The webauthor thanks 16th Ohio descendant Rob Garber for his excellent research on the Camp And Field articles and for performing the tedious digital transcription of those articles found on each page. The transcriptions were made to reflect the original articles verbatim, misspellings and all. Rob is the 3rd great nephew of Capt. William Buchanan, Company F, 16th Ohio, who served in the 90-day regiment as a private, re-enlisting in the three year regiment, and eventually making the rank of Captain of Company F. Thanks Rob!

Chapter 66 - November/December, 1863

|

Published in Holmes County Republican LXVI. Plenty of the boys felt well enough to try their Small articles from a lot of Sutlers' stores, in the hold, began to find their way to the deck. The Sutler tried to recover his missing goods but failed to find them, so he stationed himself at the hatchway with a piece of chalk and whenever a suspicious looking fellow came up he chalked his back. The foraging was stopped but the lost property was never recovered nor the foragers brought to justice. Hundreds of sea gulls kept in the vicinity of the vessel, ever on the wing, and uttering a peculiar cry of but one note. Any edible thing that was thrown into the water was skillfully picked up by these tireless, watchful birds. A schooner under full canvass, far ahead to the larboard of our course, was bearing away before a stiff breeze. Failing to run up their colors, Captain Barstow, of the St. Mary, ordered chase and under fore-sail and steam we gained steadily. Coming in range, one of the three ten-pounders on our ship was fired, the ball striking the water ahead of the schooner. The next went over and made a splash beyond. The schooner then On the 27th a cold wind was blowing from the north-west. As the day advanced it increased. That night we passed the lights of Pass Cavalla, mouth of Matagorda Bay. The 28th was a rough day. The wild waves, crested with white caps, completely environed us and extended to the horizon. The good ship, buffered by the violent sea, rolled and plunged, sometimes careening so that a wheel would be almost entirely out of water, and coils of rope and other material on deck would slide. One minute the vessel would be reared up with the bowsprit high in air, the next the stern would be lifted almost clear of the surface. Frequently, as the big waves struck us, the salt spray went over the decks and sprinkled the soldiers that were hanging on to anything immovable to keep right end up. Our supply of fresh water was kept in casks down in the hold. Daily it was issued to us the same as other rations. To-day, as our water was being hoisted up to us, the tackle became detached as it reached the deck and a lurch of the ship sent the cask with our day's rations of fresh water thumping and tumbling down into the sea. That night we dropped anchor off Padre Island, but before morning we were obliged to hoist anchor and put out to sea. In the management of the ship in the darkness and roaring storm, the regular crew was insufficient and help was called for among the soldiers. The latter being bunked down for the night didn't feel so much concern as the peril of the situation probably demanded, therefore failed to comply with the ship officer's stern appeals for help. When the voice of the sea-captain was heard in the lightless cabin, calling on the boys to give a hand at the anchor or they would |

tion. Having been officially informed that Fort Esperanza, on the west side of Pass Cavalla, was in the hands of our troops, we steamed for that place. The garrison had evacuated the fort, blew up the magazine and retreated toward Indianola, sixteen miles inland, when a force of our men, that had approached at Aransas Pass were approaching. Besides the fort, nine large siege guns remained as trophies. On Dec. 1st we were outside the bar, every man eager to land. Some boys had been sick during the whole voyage and it was reported that a few had not tasted food for six days. Gen. Lawler was in his bunk about all the time, Before leaving Algiers, two Company B boys, Ed. McCoy and Newt. Gorsuch laid in a box of choice provisions for the trip, but when they got to sea Ed. got fearful sick and remained so until we landed in Texas. Newt. stayed well and ate the Dec. 2d we entered the pass, sounding our way carefully, slowly approaching Decrow's Point, the extreme point of Matagorda Peninsula. A minute after the leadsman had called out Where we landed there had once been a village which was flooded and swept away by the wind tide during a The landing of troops continued industriously; camps were pitched, and after several days a clever little army was together. The land was all sand and sea shell. Some grass grew, but there was much more sage weed and plenty of sand bur. The latter was a bad thing to step on with bare feet. The two families used cistern water for drinking and cooking. Tolerable fair water could be found by digging down a couple of feet in the sand. If we went too deep the water was salty. Fuel for cooking was an important item. The drift along the shore supplied us temporarily. Good weather was sprinkled in with the bad. A part of the time it was very mild and summer-like, then the boys indulged in sea bathing. The soap we brought along did not work at all with the salt water. Instead of making a lather, when rubbed on the skin, it only riveled up. After a while we received a soap made expressly for salt water. When off duty, if the weather permitted, hours were devoted to hunting shells along the beach. Some very fine specimens were found. |

| Camp & Field Chapter 65 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 67 |