| Camp & Field Chapter 37 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 39 |

The Camp & FieldArticles by Theodore Wolbach |

Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach |

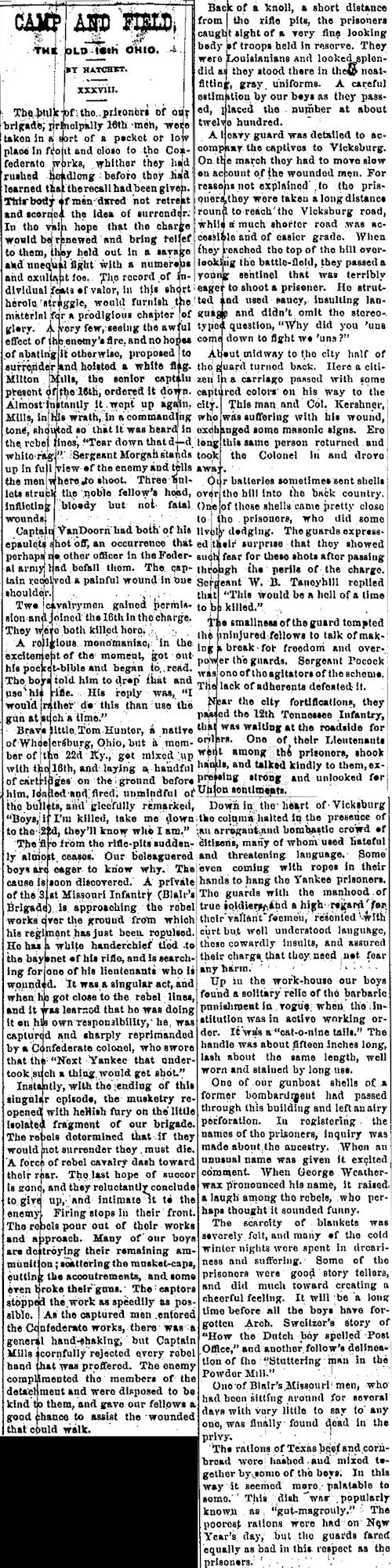

The following image represents one of a series of articles written by Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach, Company E, titled "Camp and Field" and published, by chapter, in the Holmes County Republican newspaper from February 24, 1881 to August 17, 1882. The articles tell the story, in great detail and color, of the 16th OVI, from the inception of the 3-year regiment in October, 1861, through all its camps, battles and marches until it was disbanded on October 31, 1864. The first 35 chapters, also presented on these pages, were obtained from a book in which the articles, clipped from the newspaper, had been pasted over the pages, believed to have been done by a descendant of Capt. Rezin Vorhes, Company H. All the remaining chapters (36 through 78), except chapter 60, were recently found in a Holmes County library by researcher Rob Garber who obtained copies, performed the transcriptions and provided to this website and which are also presented here, thus providing the complete work by Theodore Wolbach.

Throughout these articles click on the underlined white text for additional details.

The webauthor thanks 16th Ohio descendant Rob Garber for his excellent research on the Camp And Field articles and for performing the tedious digital transcription of those articles found on each page. The transcriptions were made to reflect the original articles verbatim, misspellings and all. Rob is the 3rd great nephew of Capt. William Buchanan, Company F, 16th Ohio, who served in the 90-day regiment as a private, re-enlisting in the three year regiment, and eventually making the rank of Captain of Company F. Thanks Rob!

Chapter 38 - January, 1863

|

Published in Holmes County Republican XXXVIII. The bulk of the prisoners of our brigade, principally 16th men, were taken in a sort of packet or low place in front and close to the Confederate works, whither they had rushed headlong before they had learned that the recall had been given. This body of men dared not retreat and scorned the idea of surrender. In the vain hope that the charge would be renewed and bring relief to them, they held out in a savage and unequal fight with a numerous and exultant foe. The record of individual feats of valor, in this short heroic struggle, would furnish the material for a prodigious chapter of glory. A very few, seeing the awful effect of the enemy's fire, and no hopes of abating it otherwise, proposed to surrender and hoisted a white flag. Milton Mills, the senior captain present of the 16th, ordered it down. Almost instantly it went up again. Mills, in his wrath, in a commanding tone, shouted that it was heard in the rebel lines, Captain VanDoorn had both of his epaulets shot off, an occurrence that perhaps no other officer in the Federal army had befall them. The captain received a painful wound in one shoulder. Two cavalrymen gained permission and joined the 16th in the charge. They were both killed here. A religious monomaniac, in the excitement of the moment, got out his pocket-bible and began to read. The boys told him to drop that and use his rifle. His reply was, Brave little Tom Hunter, a native of Wheelersburg, Ohio, but a member of the 22d Ky., got mixed up with the 16th, and laying a handful of cartridges on the ground before him, loaded and fired, unmindful of the bullets, and gleefully remarked, The fire from the rifle-pits suddenly almost ceases. Our beleaguered boys are eager to know why. The cause is soon discovered. A private of the 31st Missouri Infantry (Blair's Brigade) is approaching the rebel works over the ground from which his regiment has just been repulsed. He has a white handerchief [sic] tied to the bayonet of his rifle, and is searching for one of his lieutenants who is wounded. It was a singular act, and when he got close to the rebel lines, and it was learned that he was doing it on his own responsibility, he was captured and sharply reprimanded by a Confederate colonel, who swore that the Instantly, with the ending of this singular episode, the musketry reopened with hellish fury on the little isolated fragment of our brigade. The rebels determined that if they would not surrender they must die. A force of rebel cavalry dash toward their rear. The last hope of succor is gone, and they reluctantly conclude to give up, and intimate it to the enemy. Firing stops in their front. The rebels pour out of their works and approach. Many of our boys are destroying their remaining ammunition; scattering the musket=caps, cutting the accouterments, and some even broke their guns. The captors stopped the work as speedily as possible. As the captured men entered the Confederate works, there was a general hand-shaking, but Captain Mills scornfully rejected every rebel hand that was proffered. The enemy complimented the members of the detachment and were disposed to be kind to them, and gave our fellows a good chance to assist the wounded that could walk. |

Back of a knoll, a short distance from the rifle pits, the prisoners caught sight of a very fine looking body of troops held in reserve. They were Louisianians and looked splendid as they stood there in their neat-fitting, gray uniforms. A careful estimation by our boys as they passed, placed the number at about twelve hundred. A heavy guard was detailed to accompany the captives to Vicksburg. On the march they had to move slow on account of the wounded men. For reasons not explained they were taken a long distance round to reach the Vicksburg road, while a much shorter road was accessible and of easier grade. When they reached the top of the hill overlooking the battle-field, they passed a young sentinel that was terribly eager to shoot a prisoner. He strutted and used saucy, insulting language and didn't omit the stereotyped question, About midway to the city half of the guard turned back. Here a citizen in a carriage passed with some captured colors on his way to the city. This man and Col. Kershner, who was suffering with his wound, exchanged some masonic signs. Ere long this same person returned and took the Colonel in and drove away. Our batteries sometimes sent shells over the hill into the back country. One of these shells came pretty close to the prisoners, who did some lively dodging. The guards expressed their surprise that they showed such fear for these shots after passing the perils of the charge. Sergeant W.B. Taneyhill replied that The smallness of the guard tempted the uninjured fellows to talk of making a break for freedom and overpower the guards. Sergeant Pocock was one of the agitators of the scheme. The lack of adherents defeated it. Near the city fortifications, they passed the 12th Tennessee Infantry, that was waiting at the roadside for orders. One of their Lieutenants went among the prisoners, shook hands, and talked kindly to them, expressing strong and unlooked for Union sentiments. Down in the heart of Vicksburg the column halted in the presence of an arrogant and bombastic crowd of citizens, many of whom used hateful and threatening language. Some even coming with ropes in their hands to hang the Yankee prisoners. The guards with the manhood of true soldiers, and a high regard for their valiant foemen, resented with curt but well understood language, these cowardly insults, and assured their charges that they need not fear any harm. Up in the work-house our boys found a solitary relic of the barbaric punishment in vogue when the institution was in active working order. It was a One of our gunboat shells of a former bombardment had passed through this building and left an airy perforation. In registering the names of the prisoners, inquiry was made about the ancestry. When an unusual name was given it excited comment. When George Weatherwax pronounced his name, it raised a laugh among the rebels, who perhaps thought it sounded funny. The scarcity of blankets was severely felt, and many of the cold winter nights were spent in dreariness and suffering. Some of the prisoners were good story tellers, and did much toward creating a cheerful feeling. It will be a long time before all the boys have forgotten Arch. Sweitzer's story of One of Blair's Missouri men, who had been sitting around for several days with very little to say to any one, was finally found dead in the privy. The rations of Texas beef and cornbread were hashed and mixed together by some of the boys. In this way it seemed more palatable to some. This dish was popularly known as |

| Camp & Field Chapter 37 | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 39 |