| Camp & Field Page 58 (Chapter 35) | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 37 |

The Camp & FieldArticles by Theodore Wolbach |

Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach |

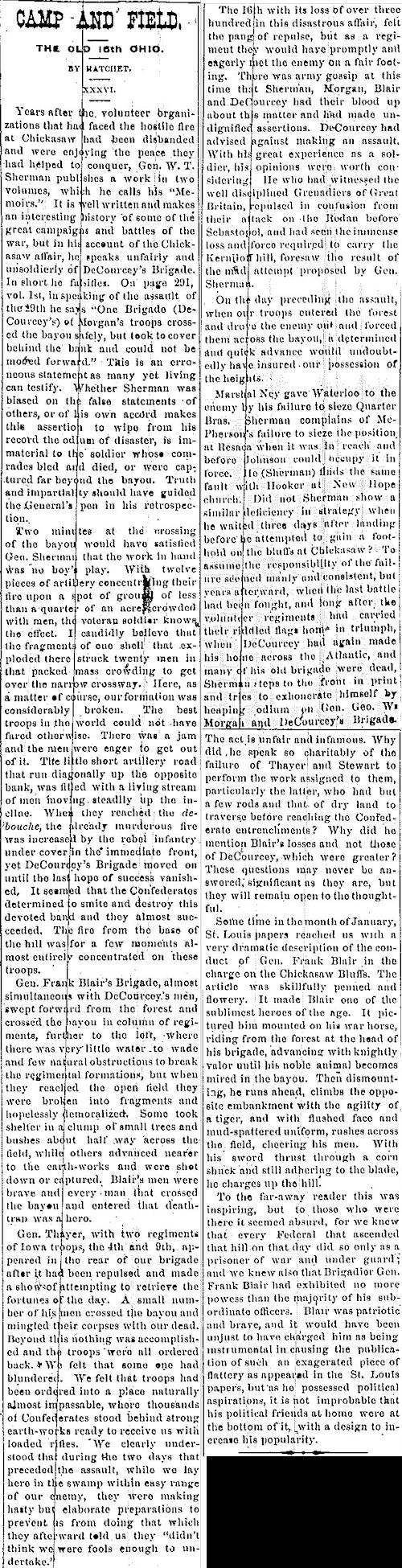

The following image represents one of a series of articles written by Cpl. Theodore D. Wolbach, Company E, titled "Camp and Field" and published, by chapter, in the Holmes County Republican newspaper from February 24, 1881 to August 17, 1882. The articles tell the story, in great detail and color, of the 16th OVI, from the inception of the 3-year regiment in October, 1861, through all its camps, battles and marches until it was disbanded on October 31, 1864. The first 35 chapters, also presented on these pages, were obtained from a book in which the articles, clipped from the newspaper, had been pasted over the pages, believed to have been done by a descendant of Capt. Rezin Vorhes, Company H. All the remaining chapters (36 through 78), except chapter 60, were recently found in a Holmes County library by researcher Rob Garber who obtained copies, performed the transcriptions and provided to this website and which are also presented here, thus providing the complete work by Theodore Wolbach.

Throughout these articles click on the underlined white text for additional details.

The webauthor thanks 16th Ohio descendant Rob Garber for his excellent research on the Camp And Field articles and for performing the tedious digital transcription of those articles found on each page. The transcriptions were made to reflect the original articles verbatim, misspellings and all. Rob is the 3rd great nephew of Capt. William Buchanan, Company F, 16th Ohio, who served in the 90-day regiment as a private, re-enlisting in the three year regiment, and eventually making the rank of Captain of Company F. Thanks Rob!

Chapter 36 - January, 1863

|

Published in Holmes County Republican XXXVI. Years after the volunteer organizations that had faced the hostile fire at Chickasaw had been disbanded and were enjoying the peace they had helped to conquer, Gen. W.T. Sherman publishes a work in two volumes, which he calls his Two minutes at the crossing of the bayou would have satisfied Gen. Sherman that the work in hand was no boy's play. With twelve pieces of artillery concentrating their fire upon a spot of ground of less than a quarter of an acre crowded with men, the veteran soldier knows the effect. I candidly believe that the fragments of one shell that exploded there struck twenty men in that packed mass crossing to get over the narrow crossway. Here, as a matter of course, our formation was considerably broken. The best troops in the world could not have fared otherwise. There was a jam and the men were eager to get out of it. The little short artillery road that runs diagonally up the opposite bank, was filled with a living stream of men moving steadily up the incline. When the reached the debouche, the already murderous fire was increased by the rebel infantry under cover in the immediate front, yet DeCourcey's Brigade moved on until the last hope of success vanished. It seemed that the Confederates determined to smite and destroy this devoted band and they almost succeeded. The fire from the base of the hill was for a few moments almost entirely concentrated on these troops. Gen. Frank Blair's Brigade, almost simultaneous with DeCourcey's men, swept forward from the forest and crossed the bayou in column of regiments, further to the left, where there was very little water to wade and few natural obstructions to break the regimental formations, but when they reached the open field they were broken into fragments and hopelessly demoralized. Some took shelter in a clump of small trees and bushes about half way across the field, while others advanced nearer to the earth-works and were shot down or captured. Blair's men were brave and every man that crossed the bayou and entered that deathtrap was a hero. Gen. Thayer, with two regiments of Iowa troops, the 4th and 9th, appeared in the rear of our brigade after it had been repulsed and made a show of attempting to retrieve the fortunes of the day. A small number of his men crossed the bayou and mingled their corpses with our dead. Beyond this nothing was accomplished and the troops were all ordered back. We felt that some one had blundered. We felt that troops had been ordered into a place naturally almost impassable, where thousands of Confederates stood behind strong earth-works ready to receive us with loaded rifles. We clearly understood that during the two days that preceded the assault, while we lay here in the swamp within easy range of our enemy, they were making hasty but elaborate preparations to prevent us from doing that which they afterward told us they |

The 16th with its loss of over three hundred in this disastrous affair, felt the pang of repulse, but as a regiment they would have promptly and eagerly met the enemy on a fair footing. There was army gossip at this time that Sherman, Morgan, Blair and DeCourcey had their blood up about this matter and had made undignified assertions. DeCourcey had advised against making an assault. With his great experience as a soldier, his opinions were worth considering. He who had witnessed the well disciplined Grenadiers of Great Britain, repulsed in confusion from their attack on the Redan before Sebastopol, and had seen the immense loss and force required to carry the Kernou hill, foresaw the result of the mad attempt proposed by Gen. Sherman. On the day preceding the assault, when our troops entered the forest and drove the enemy out and forced them across the bayou, a determined and quick advance would undoubtedly have insured our possession of the heights. Marshal Ney gave Waterloo to the enemy by his failure to sieze [sic] Quarter Bras. Sherman complains of McPherson's failure to sieze the position at Resada when it was in reach and before Johnson could occupy it I force. He (Sherman) finds the same fault with Hooker at New Hope church. Did not Sherman show a similar deficiency in strategy when he waited three days after landing before he attempted to gain a foothold on the bluffs at Chickasaw? To assume the responsibility of the failure seemed manly and consistent, but years afterward, when the last battle had been fought, and long after the volunteer regiments had carried their riddled flags home in triumph, when DeCourcey had again made his home across the Atlantic, and many of his old brigade were dead, Sherman steps to the front in print and tries to exhonerate [sic] himself by heaping odium on Gen. Geo. W. Morgan and DeCourcey's Brigade. The act is unfair and infamous. Why did he speak so charitably of the failure of Thayer and Stewart to perform the work assigned to them, particularly the latter, who had but a few rods and that of dry land to traverse before reaching the Confederate entrenchments? Why did he mention Blair's losses and not those of DeCourcey, which were greater? These questions may never be answered, significant as they are, but they will remain open to the thoughtful. Some time in the month of January, St. Louis papers reached us with a very dramatic description of the conduct of Gen. Frank Blair in the charge on the Chickasaw Bluffs. The article was skillfully penned and flowery. It made Blair one of the sublimest heroes of the age. It pictured him mounted on his war horse, riding from the forest at the head of his brigade, advancing with knightly valor until his noble animal becomes mired in the bayou. Then dismounting, he runs ahead, climbs the opposite embankment with the ability of a tiger, and with flushed face and mud-spattered uniform, rushes across the field, cheering his men. With his sword thrust through a corn shuck and still adhering to the blade, he charges up the hill. To the far-away reader this was inspiring, but to those who wee there it seemed absurd, for we knew that every Federal that ascended that hill on that day did so only as a prisoner of war and under guard, and we knew also that Brigadier Gen. Frank Blair had exhibited no more powess [sic] than the majority of his subordinate officers. Blair was patriotic and brave, and it would have bee unjust to have charged him as being instrumental in causing the publication of such an exagerated [sic] piece of flattery as appeared in the St. Louis papers, but as he possessed political aspirations, it is not improbable that his political friends at home were at the bottom of it, with a design to increase his popularity. |

| Camp & Field Page 58 (Chapter 35) | Camp & Field Index Page | 16th OVI Home Page | Camp & Field Chapter 37 |