| Previous Facts & Stories | Facts & Stories Index | 16th OVI Home Page | Next Facts & Stories |

of the 16th Ohio Volunteer Infantry

June 3, 1861

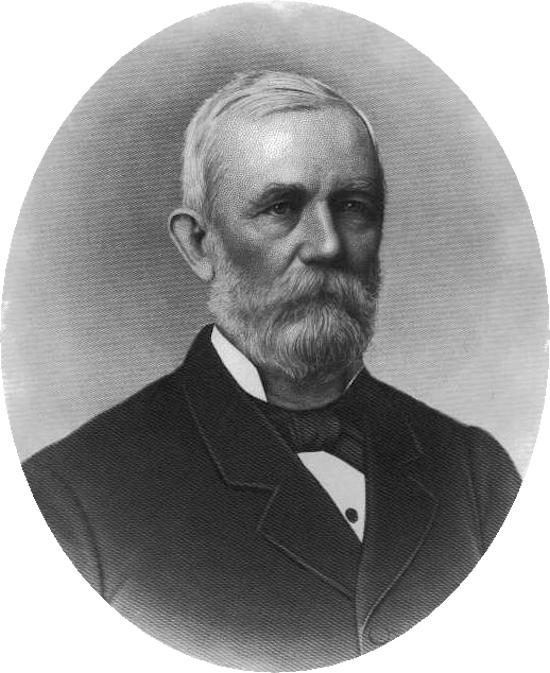

It is well documented that the first amputation of the Civil War was performed shortly after the first land battle of the war at Phillip, (West) Virginia. The amputation was performed by 16th Ohio surgeon James Robison on a Confederate soldier who, later, put his misfortune to very good use.

From Pat Granstra's Civil War Primer:

Throughout the morning of June 3, 1861, a young Confederate soldier lay unconscious and bleeding in a stable near Philippi, in northwest Virginia (now West Virginia). Four hours after a Union cannonball tore through his left thigh, soldiers of the 16th Ohio Volunteers found him and summoned their surgeon, Dr. James D. Robison, to the scene.

Determining that the lad's life could be saved only by immediate amputation, Dr. Robison performed surgery on a table improvised from a stable door. During a 45-minute operation (done without benefit of anesthetic), he removed the young Confederate's leg seven inches below the hip and stitched a flap of skin over the wound. Dr. Robison did not know he had completed the first of over 50,000 Civil War amputations. He also did not know that the successful outcome of his surgery would impact not only his patient but also thousands of amputees long after the war.

*****

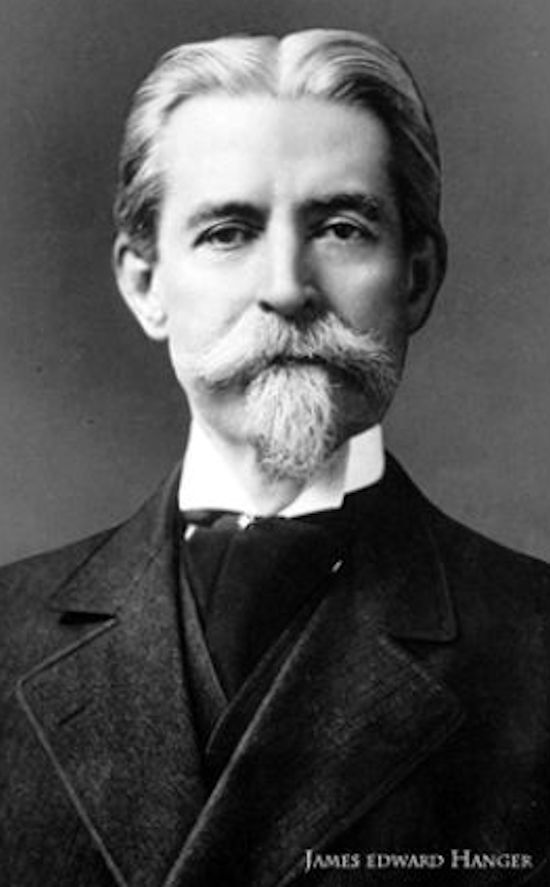

Robison's patient was eighteen-year-old James Hanger [Churchville Cavalry/14th Virginia Cavalry Regiment] from Churchville, Virginia. A sophomore majoring in engineering at Washington College in Lexington at the start of the war, Hanger chose the Confederacy over the classroom and returned to Churchville to enlist in the town's cavalry troop as two of his older brothers had done. He was not among the original enlistees, but when an ambulance corps rolled through town on its way north to support the Churchville Cavalry and other Confederate forces under Colonel George Porterfield, young Hanger rode with it.

Outside Philippi on the evening of June 1, the ambulance corps encountered the Churchville Cavalry among Confederate forces retreating south before vastly superior Union forces. Along with several other young men, he enlisted the next day. The night of June 2 brought heavy rain, and as Hanger later wrote, the new soldiers "did not move, perhaps on account of the rain and the belief that the enemy would not march in such rain and darkness.

In reality, the more experienced Union soldiers, two columns of them, had marched, intending to trap the rebels between them at Philippi. The weather had not deterred them, but it did upset their timing. One column fired its opening shots before the other was in position, a misstep that afforded most of the southern soldiers an escape route.

Writing later, Hanger claimed he was hit by the third shot of a skirmish newspapers ostentatiously heralded as the first land battle of the Civil War. "The first two shots," he wrote, "were canister and directed at the Cavalry Camps, the third shot was a 6 pound solid shot aimed at a stable in which the Churchville Cavalry Company had slept. This shot struck the ground, richochedtted [sic], entering the stable and struck me.

Robison's quick action and surgical skill saved Hanger's life, and competent post-operative care, first in a private home and later in a Union hospital near Philippi, prompted a quick recovery. Within a few weeks, Hanger's stump healed sufficiently for him to be fitted with a wooden leg and sent to Camp Chase near Columbus, Ohio. He next went to Norfolk, Virginia as part of a prisoner exchange and returned to his parents' home near Churchville in August.

In Private Hangar's own words:

We were ordered to pack up and be ready to move on a moments notice. About dark we were notified that we would not move until midnight. Early in the night it commenced to rain and rained hard until nearly daylight. At midnight we did not move, perhaps on account of the rain and the belief that the enemy would not march in such rain and darkness…the Federals were moving in on us and would be there soon, and were entirely too strong for our forces equipped as we were, not a single cartridge in the command, only loose powder, ball and shot. Arms – old flintlock muskets, horse pistols, a few shotguns and colt revolvers…

As the Co. [column] on the Clarksburg road passed old Mrs. Humphrey's home about 2 miles from Philippi about daybreak, she started one of her boys to notify our command. Her boy was captured by some stragglers and she fired a gun at then. The commander of the battery took this for the [prearranged] signal and commenced firing about 4:20 a.m. He told me that this firing was the first notice we had that the enemy were near us. The Col. that was to cut off our retreat was delayed some 30 or 40 minutes on account of heavy roads, which gave our forces time to get away.

The first two shots were canister and directed at the Cavalry Camps, the third shot was a 6 pound solid shot aimed at a stable in which the Churchville Cavalry Company had slept. This shot struck the ground, richochetted [sic], entering the stable and struck me. I remained in the stable til they came looking for plunder, about four hours after I was wounded. My limb was amputated by Dr. Robinson, 16th Ohio Vol.

Writer Martha M. Boltz wrote the following which appeared in a Washington Times publication on June 8, 2011:

Hanger's injury had come on June 3, a day after his enlistment, in the skirmish at Philippi. When he leaped from the hayloft of the barn to get his horse moved to safety, the ricocheting ball struck and shattered his leg, requiring amputation above the knee.

Interestingly enough, Hanger's was not the only amputation of the skirmish. His came several hours after his capture, when he was found wounded in the Garrett Johnson barn. Realizing the extreme blood loss and the severity of his injury, it was decided that only immediate amputation would save his life, and the Union doctor, Dr. James Robinson called for the barn door to be taken off and utilized into a makeshift operating table.

There was no anesthesia available, and it took about 45 minutes to complete the surgery and construct a proper flap of the remaining skin over the stump, removing the leg about 7" below the hip and above the knee.

At about the same time that Hanger was injured, another Rebel soldier, a Capt. Daingerfield, also sustained a leg injury when a minie ball shattered his knee. A Confederate surgeon, Dr. John T. Huff, was forced to amputate Daingerfield's leg with a butcher knife and carpenter's saw the next day, on June 4.

Thus James Hanger and Capt. Dangerfield became the first two amputees of the war.

Hanger was then moved to the Philippi Methodist Episcopal Church which had been converted into a hospital, and from there to the home of a couple who lived nearby, Mr. and Mrs. William McClaskey.

As Southern sympathizers, they were happy to have the young man and cared for him in whatever way was needed.

Soon the Union army took over their home, and James was again moved, this time to a farm in the country known as Cherry Hill, already converted to a hospital for the injured. Here young James probably was given his first artificial leg. It amounted to a straight, heavy wooden device strapped to the stump, the original "'peg leg'", characterized by its total lack of mobility and the thumping noise it made, which could be heard quite a distance away.

Amputation in that era frequently carried a death sentence; recovery was long and arduous, care was difficult to manage in or around a battlefield, and post surgical infection ran rampant, upping the mortality rate to about 52% if the amputation was delayed after 48 hours.

Following up on Confederate soldier Edward Hanger's post-amputation life, from Wikipedia:

Dissatisfied with both the fit and the function of his above-knee prosthesis, Hanger designed a new prosthesis constructed of whittled barrel staves and metal. His design used rubber bumpers rather than standard catgut tendons and featured hinges at both the knee and foot. Hanger patented his limb in 1871 and it has received numerous additional patents for improvements and special devices which have brought international reputation to the product. The Virginia state government commissioned Hanger to manufacture the above-knee prosthesis for other wounded soldiers. Manufacturing operations for J.E. Hanger, Inc., were established in the cities of Staunton and Richmond. The company eventually moved to Washington, D.C.

Other inventions credited to Hanger include a horseless carriage (used as a toy by his children); an adjustable reclining chair; a water turbine; a Venetian blind; and a lathe used in the manufacturing process for prosthetic limbs.

Hanger married Nora McCarthy in Richmond in 1873. The couple had two daughters (Princetta and Alice) and six sons (James Edward, Herbert Blair, McCarthy, Hugh Hamilton, Henry Hoover and Albert Sidney). The family moved to Washington, D.C., in the 1880s, and their home near Logan Circle still stands today. All of Hanger's sons worked in the family business as adults.

Hanger retired from active management of the company in 1905, however he retained the title of president. In 1915, he traveled to Europe to observe firsthand the latest techniques of European prosthetists. As a result, the company received contracts with both England and France during and after World War I. At the time of Hanger's death in 1919, the company had branches in Atlanta, St. Louis, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, London and Paris.

Hanger's children and grandchildren, along with in-laws, cousins and other associates, continued operating and expanding the company. By the mid 1950s there were 50 Hanger offices in North America and 25 in Europe. In 1989, J. E. Hanger, Inc. of Washington, D.C., was purchased by Hanger Orthopedic Group, Inc. and became part of their wholly owned subsidiary, Hanger Prosthetics and Orthotics. According to the company's 2007 annual report, net sales for this patient care services segment were $571.7 million. As of 2008, Hanger Prosthetics & Orthotics sees about 650,000 patients annually.

James Edward Hangar

Dr. James Dickey Robison

| Previous Facts & Stories | Facts & Stories Index | 16th OVI Home Page | Next Facts & Stories |